by Cunningham Geikie, D.D.

by Cunningham Geikie, D.D.

Philologos Religious Online Books

Philologos.org

Chapter 19 | Contents | Chapter 21

Cunningham Geikie D.D.

With a Map of Palestine and Original Illustrations by H. A. Harper

Special Edition

(1887)

The small dimensions of Palestine are very forcibly brought before the mind by the discovery that the chief scenes of David's life, before he reigned in Jerusalem, lie within a circle of not more than twelve or fifteen miles round his native village. It was only a three or four hours' journey for the boy from Bethlehem to Saul's camp at Socoh; and by starting early, as he would, he could readily have been among the fighting men in the beginning of the forenoon, so as to leave abundant time for his magnificent duel with Goliath. For one so strong and active it would be little to go on his venturous challenge down the

stony, brushwood-covered hill on which his brothers and the other Hebrews stood drawn up, across the half-mile of broad, flat valley, now covered every season with grain, then over the narrow trench in the middle full of white pebbles worn by the rain; nor would it have been more than a youth could do without special effort, to return again the same night to his father's house in Bethlehem. Adullam, Keilah, Carmel, Ziph, all lie within a small circle: David's adventures, indeed, during several years, may all be followed in a space smaller almost than any of our English counties.

The small dimensions of Palestine are very forcibly brought before the mind by the discovery that the chief scenes of David's life, before he reigned in Jerusalem, lie within a circle of not more than twelve or fifteen miles round his native village. It was only a three or four hours' journey for the boy from Bethlehem to Saul's camp at Socoh; and by starting early, as he would, he could readily have been among the fighting men in the beginning of the forenoon, so as to leave abundant time for his magnificent duel with Goliath. For one so strong and active it would be little to go on his venturous challenge down the

stony, brushwood-covered hill on which his brothers and the other Hebrews stood drawn up, across the half-mile of broad, flat valley, now covered every season with grain, then over the narrow trench in the middle full of white pebbles worn by the rain; nor would it have been more than a youth could do without special effort, to return again the same night to his father's house in Bethlehem. Adullam, Keilah, Carmel, Ziph, all lie within a small circle: David's adventures, indeed, during several years, may all be followed in a space smaller almost than any of our English counties.

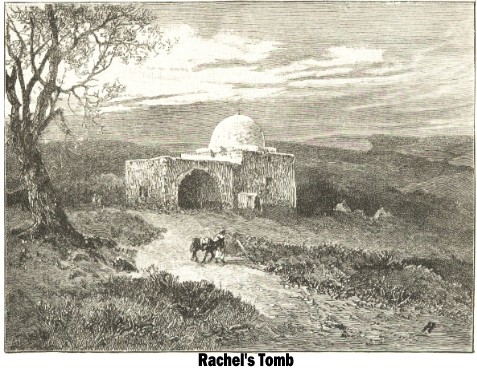

But it was time to leave this most interesting spot, where, in David's own words—called forth, it may be, by the scenery round his native town—"the little hills rejoice on every side: the pastures are clothed with flocks, and the valleys are covered over with corn" (Psa 65:13). It takes but a few minutes to strike a tent, and a very short time to pack it on the backs of the patient donkeys, so that we were soon on the way to Jerusalem. The road was thronged with town and country people, going to their gardens, or bringing loads from them. Asses quietly pattered on beneath huge burdens of cauliflowers large enough to rejoice the heart of an English gardener. Camels stalked up the hill with loads of building-stone: their drivers with clubs in their girdles. Men and women, in picturesque dress, passed this way and that as we jogged down towards Pilate's Aqueduct, which runs level with the ground, or nearly so, is covered with flat unhewn stones, and would be overlooked as only a common wall but for openings at intervals through which the running water is seen. The road turns straight to the north, with stony fields on the right, and a narrow open hollow of olives on the left, the ground slowly rising on this side, however, till at Rachel's grave, about a mile from Bethlehem, there is for the time a level space, well strewn, as usual, with stones of all sizes.

The place where the mother of Joseph and Benjamin, the patriarch Jacob's early and abiding love, is buried, is one of the few spots respecting which Christian, Jew, and Mahommedan agree. The present building consists of four square walls, each twenty-three feet long, and about twenty feet high, with a flat roof, from which a dome, with the plaster over it in sad disrepair, rises for about ten feet more. The masonry is rough: the stones set in rows, with no attempt at finish, or even exact regularity. Originally there was a large arch in each of the walls, which between them enclose an open space, but these arches have at some time been built up. The building dates, perhaps, from the twelfth century, though the earliest notice we have of it is a sketch in an old Jewish book of the year AD 1537. Joined to the back of it is another building consisting of four stone walls coarsely built, about thirteen feet high, the space enclosed being thirteen feet deep and twenty-three feet broad—that is, as broad as the domed building; with a flat roof. Behind this again the walls are continued, at the same height, for twenty-three feet more each way, forming a covered court, used for prayer by the Mahommedans. Under the dome stands an empty tomb of modern appearance, but entrance to this part, and also to the second chamber, is in the hands of the Jews, who visit it on Fridays. The pillar erected by Jacob has long since disappeared, having apparently been replaced at various times by different constructions. No part of the present building, I may say, except the high domed part, is older, apparently, than the present century.

The stone raised by Jacob in memory of his much-loved wife has been turned to wonderful account by recent "advanced critics" of the Old Testament, who have founded on this simple act the astounding assertion that Jacob and the patriarchs were sun-worshippers, and this poor headstone an idolatrous sun-pillar, such as were set up in the temples of Baal and Astarte, the foul gods of Canaan.* This amazing theory rests, like a pyramid on its sharp end, on the minute fact that the word for the obelisks raised to the sun-god was used also for such memorials as this tombstone to Rachel, or that erected in attestation of the covenant between Jacob and Laban, or for the stone set up by Jacob himself at Bethel on his return to Canaan, as a witness to the second covenant made with him there by Jehovah (Gen 28:18,22, 31:13,45,51,52, 35:14). Twelve similar stones, described by the same word, were erected by Moses when the Twelve Tribes accepted the covenant made with them by God (Exo 24:4-7): to remain a permanent proof of their having done so, and a silent plea for their fidelity. Did the great law-giver who proclaimed, "Hear, O Israel, Jehovah, our God, is one Jehovah" (Deut 6:4 [Heb.]), and commanded that Israel should have no other gods before Him, or make any graven image, or likeness of anything in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, or in the water under the earth (Exo 20:3,4)—did this earnest and lofty soul, filled with loyalty to the one living and true God, set up twelve sun-pillars in honour of Baal? Credulity has gone a great way when it can believe this, nor can much be said for the modesty which would suggest it.

I own to a specially kindly feeling to Jacob from the story of his affection for his first love. How tender it was, is seen, as has been noticed already, by his going back to the scene of her death in his dying conversation with Joseph, more than forty years after he had lost her (Gen 48:7). The headstone at Bethlehem was still before his eyes, in these last hours of his life, and she was as precious to him then as when she first won his heart, seventy years before. He had faults, and great ones, but the man who is capable of an unchanging love has a great deal in him to respect.* Robertson Smith, Old Test. in the Jewish Church, pp. 226, 353.

It is striking how much there is in the story of the patriarchs which the manners of the East even yet illustrate. The sending of Eliezer to Mesopotamia to get a wife for Isaac is exactly what the sheikh of an Arab tribe would do to-day. A Bedouin always marries in his own clan, and will take any trouble to do so, and the same custom prevails among the Hindoos;* while there was a strong religious motive in the directions of Abraham on this point—to keep his descendants from going over to the idolatry of Canaan (Gen 24:6). What Isaac was doing when Rebekah came in sight has been vigorously disputed. Our Bible tells us he had gone out to meditate (Gen 24:63), but a great German scholar maintains that he had gone out to collect dry stalks and weeds for the evening fire,** showing no little ingenuity in defence of his novel interpretation, which, indeed, had already been suggested by some of the Rabbis. He could, to be sure, meditate while at his task, for one need not be idle to turn his thoughts in a serious direction, and in the East no detail of tent life is beneath a sheikh's personal attention; for we are told that even the great Abraham ran to the herd and, himself, "fetched a calf, and gave it to a young man, to kill and dress for his visitors" (Gen 18:7). Just as an Arab bride would do now in being brought to her future husband, Rebekah "lighted off the camel" and veiled herself (Gen 24:64,65), because she would not ride while he was on foot, and she could not allow her face to be seen till she was his wife.

Isaac had been brought up, in childhood, in his mother Sarah's part of the tent, shut off from the men's part, and thither he took his bride, fortunately "loving her" when now for the first time he saw her. She would be led to it by her nurse and her maids who had come with her, but, one by one, these would leave her, till she was all alone with the nurse, wondering whether she would please Isaac when he came. After a time, the nurse would throw a shawl over her head, and, a signal having been given, the curtain would be pushed aside for a moment, and the bridegroom would enter, and the nurse withdraw. Man and wife would thus for the first time be face to face. Now came the moment for removing the veil, or shawl, that hid the bride's face. If he had been a modern Oriental, Isaac would have said, "In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful," and, then, raising the shawl, would greet his wife with the words, "Blessed be this night," to which her answer would be, "God bless thee." This was the first time Isaac had seen Rebekah unveiled, and it would be an anxious matter for the nurse and the maids, and, above all, for Rebekah herself, whether she pleased or disappointed her husband, for there might have been an anticipation of Jacob's trouble, by finding a Leah instead of a Rachel. But Rebekah's face pleased her future lord, as, indeed, the face of the bride generally does please a bridegroom, and he would announce this fact to the anxious women outside, who, forthwith, no doubt, set up a shrill cry of delight, just as their sisters who stand in the same relation to a young wife do now. To the Semitic races this shout of the triumphant and satisfied bridegroom is one of the most delightful sounds that can be uttered, and has been so for immemorial ages; and it is to this that John the Baptist alludes when he says, "He that hath the bride is the bridegroom; but the friend of the bridegroom, who standeth and heareth him, rejoiceth greatly because of the bridegroom's voice" (Ebers, Egypt, ii. 96; John 3:29).* Rosenmuller, A. u. N. Morgenland, i. 102.

** Bottcher, Aehrenlese, i. 19.

The character of Jacob was a duplicate of that of his mother. As her pet, she trained him, perhaps unconsciously, in her own faults, and he was clearly an apt scholar. The sister of Laban, a man full of craft and deceit like most Arabs, was not likely to be very open or straightforward. To make a favourite of one of a family, at least so as to show preference, is a sign of narrow, though perhaps deep, affection; but to overreach a husband like Isaac, for the injury of one of her two sons, was as heartless as it was ignoble. The wonder is that, with such a mother, Jacob was, in the end, even as worthy as he proved himself. His being a plain man, living in tents (Gen 25:27), points to the contrast between the wild unsettledness of his brother and his own quiet, or, we might say, "domesticated" nature, and so does his life as a shepherd, roving about with his flocks and tents—a life, greatly honoured among the Hebrews—while Esau spent his days in what they thought the rough, savage pursuits of a hunter. The red pottage of lentils for which Jacob bought the birthright (Gen 25:30), is still a favourite dish among the poorer classes in the East; the lentils being first boiled, and then made tasty by mixing some fat with them,* or olive-oil and pepper. Barzillai, it will be remembered, brought a quantity of them, among other things, with him to Mahanaim, as a gift to David, during the rebellion of Absalom; and we find that in times of scarcity in the days of Ezekiel they were mixed with wheat and other grain, including spelt, to make bread (Eze 4:9). Lentils are still grown in great quantities in Egypt, and largely in Palestine, where one might think them peas, at an early stage of their growth, for they rise only to a height of six or eight inches, and have tendrils and pods like the pea, though purple, not green. In England and Wales they are grown as food for cattle, though it would be a blessing for the peasantry if they recognised their rich nutritiousness, and used them for themselves. European children born in Palestine are passionately fond of lentil porridge; nature, unchecked by prejudice, turning eagerly to that which it finds best suited to its wants. Two kinds of the plant are grown, the brown and the red; the latter being the better.

The deceit of Rebekah and Jacob was sorely visited on both. It must have been a great trial to the mother to lose her favourite son for ever, for Jacob not only never saw his mother again, but lost all the fruit of his years of toil under his father, and had to begin the world again in Mesopotamia, with a very hard master; spending more than twenty years before he had flocks enough to be independent of him. But Isaac was not free from blame, for a father should not show favouritism in his family, especially if it rest to a large extent on so poor a basis as the love of savoury meat (Gen 27:4). The gazelles which Esau hunted still abound in the Negeb, where Isaac had his tents; and it must have tasked Rebekah's skill to disguise a young kid so as to give it the flavour of the wild creature. It may seem strange to read that Isaac "smelled" Jacob's clothes (Gen 27:27), but in India, to this day, a similar custom prevails; so that parents will compare the smell of a child to that of a fragrant plant, and a good man will be spoken of as having a sweet smell.** Robinson, Bib. Res., i. 246.

The stone at Bethel (Gen 28:11) would have been a hard pillow for a European, but the thick turban of the Oriental, and the habit of covering the head with the outer garment during sleep, would make a cushion. The meeting with Rachel, like that of Eliezer with Rebekah, is true, in the minutest touches, to Eastern life. Abraham's deputy makes his camels kneel down, without the city, "by a well of water, at the time of evening; the time that women go out to draw water"; and so would an Arab now. Wells are commonly, though not always, just outside the towns; and it is not only correct that evening is the time for drawing water, but that the task falls to the women. The peasant is then returning from his labour in the field, or driving home his small flock, and his wife and daughters have the evening meal to prepare, for which water is needed. It is, moreover, the cool of the day. At any Eastern village you meet long files of women thus occupied. That Rebekah should have carried her water-jar on her shoulder is another touch of exactness, for Syrian women still carry the jar thus, while in Egypt it is balanced on the head.* Roberts, Indian Illustrations.

It is striking, when we think of the place of our Saviour's birth, to read of the camels being brought into Laban's house (Gen 24:31,32). I have often seen beasts thus put up with the household. In the same way we can restore the whole narrative of Jacob's meeting with Rachel (Gen 29), from everyday life in the East at the present time. The well is in the field; that is, in the open pasture-land. Water being scarce, all the flocks, for miles round, meet at it to be watered. The heavy stone rolled over its mouth may be seen by any traveller in many parts of Palestine. The daughters of the flock-masters still go, in many places, to tend and water the flocks. You may see them thus engaged near almost any Arab tents in the plain of Sharon or of Philistia. That Laban kissed Jacob effusively is only what one sees Orientals doing every day, on meeting a neighbour or friend. The wily Syrian, in admitting that it was better to give Rachel to the son of Isaac than to another man, acted simply on the Bedouin law that a suitor has the exclusive right to the hand of his first cousin, so that even if he do not himself wish to marry her, she cannot be married without his consent. To give a female slave to a daughter, as a part of her dowry, is usual now, where means permit, so that Zilpah's being given to Leah at her marriage is another proof of the unchanging sameness of Eastern life in all ages. Excuses for sending home an elder daughter, instead of a younger, to the bridegroom, need still to be made in not a few cases, and are exactly the same as those with which Laban palliated the substitution of Leah for Rachel.

The mandrakes found by Reuben, and craved by Rachel, are still in demand among Eastern women, in the same belief that they quicken love, and have other related uses. The plant is not rare in Palestine, and ripens in April or May. It has long, sharp-pointed, hairy leaves, of a deep green, springing from the ground, with dingy white flowers splashed with purple, and fruit which the Greeks called "love-apples," about the size of a nutmeg, and of a pale orange colour; the root striking down like a forked carrot. It is closely allied to the deadly nightshade, and has in all ages been famed, not only among women, but among men, in the latter case for its qualities as an intoxicant. From Leah and Rachel the interest in the mandrake passed down through each generation of their Hebrew descendants, so that we find its smell very appropriately introduced in the Song of Songs by the lovesick maiden, as awaiting her beloved in the vineyard (Song 7:13).

The teraphim of Laban, carried off by Rachel, open a curious chapter in the history of old Jewish religion. They were images, small enough to be stored in the large saddle-bags, or panniers, of Rachel's camel, and thus evidently much below the human size, and were regarded by Laban as his gods, the possession of which was of vital importance. Rachel, no doubt, shared in his opinion of their supernatural power, and had taken them, we may well suppose, that they might transfer to her husband some of the advantages of which he had been unjustly defrauded by her father. By Josephus they are called household gods,* which it was usual for the owner to carry with him for good fortune, if he went to a distance from home. How Laban made use of them is not told, though he speaks in one place of "divining" (Gen 30:27 [Heb.]), and probably did so by consulting them as oracles; just as we find Joseph, in Egypt, divining by a cup (Gen 44:5), perhaps by the movements of water in it or of substances put into the water; the fondness for such superstition clinging to him through his mother. If we may judge from later instances, Laban's teraphim were decked with an ephod, as a medium for divine communications—a broad ornamented belt round the body, reaching from the armpits to the lower ribs; held in place by a strap or girdle of the same material, and also by cords from a broad collar or cape of the same stuff covering the shoulders.**

* Jos. Ant., xviii. 9, 5.

** Riehm, p. 387.

It was on the front of such an ephod that the Jewish high priest, in later times, wore the oracular Urim and Thummim. Thus Micah, in Mount Ephraim, "had an house of gods, and made an ephod and teraphim," which Jonathan, the apostate descendant of Moses, whom Micah had made his priest,

carried off to Dan, and used there for idolatrous worship (Judg 17:5, 18:18-20). The ephod, indeed, is mentioned in connection with teraphim as late as the time of Hosea, just before the overthrow of the Ten Tribes (Hosea 3:4). The Danites evidently believed in the oracular power of such a combination, since the discovery of it in Micah's possession led them at once to the conclusion that they could use it to see what they were to do next, in their adventurous journey on the war-path in search of a new home (Judg 18:4,5). House-gods, in various forms, have always, indeed, been a great feature in idolatrous systems. Thus in the ruins of the great palace of Khorsabad, at Nineveh, Botta discovered under the threshold of the gates a number of statuettes in baked clay; images of Bel, Nergal, and Nebo, placed there, as an inscription tells us, "to keep away the wicked, and all enemies, by the terror of death."* Different parts of a house were placed under the protection of separate divinities; and a magic formula, which has been discovered, directs that a small image of one god ought to be placed at the court-gate of a house; of another, in the ground near the bed; of a third, inside the door; of a fourth, under the threshold of the door, at each side. We do not know of the Hebrews carrying their superstition so far as this, but the protection sought by means of the teraphim is closely allied to it, and the Israelites certainly sprang from an idolatrous stock, for Joshua states that their fathers, who dwelt on the other side of the Euphrates, served other gods than Jehovah (Josh 24:2). Indeed, this ancestral tendency lingered among them till extirpated by the sharp discipline of the Captivity, and even after their return they could not wean themselves from dabbling in some forms of the black art.

It was on the front of such an ephod that the Jewish high priest, in later times, wore the oracular Urim and Thummim. Thus Micah, in Mount Ephraim, "had an house of gods, and made an ephod and teraphim," which Jonathan, the apostate descendant of Moses, whom Micah had made his priest,

carried off to Dan, and used there for idolatrous worship (Judg 17:5, 18:18-20). The ephod, indeed, is mentioned in connection with teraphim as late as the time of Hosea, just before the overthrow of the Ten Tribes (Hosea 3:4). The Danites evidently believed in the oracular power of such a combination, since the discovery of it in Micah's possession led them at once to the conclusion that they could use it to see what they were to do next, in their adventurous journey on the war-path in search of a new home (Judg 18:4,5). House-gods, in various forms, have always, indeed, been a great feature in idolatrous systems. Thus in the ruins of the great palace of Khorsabad, at Nineveh, Botta discovered under the threshold of the gates a number of statuettes in baked clay; images of Bel, Nergal, and Nebo, placed there, as an inscription tells us, "to keep away the wicked, and all enemies, by the terror of death."* Different parts of a house were placed under the protection of separate divinities; and a magic formula, which has been discovered, directs that a small image of one god ought to be placed at the court-gate of a house; of another, in the ground near the bed; of a third, inside the door; of a fourth, under the threshold of the door, at each side. We do not know of the Hebrews carrying their superstition so far as this, but the protection sought by means of the teraphim is closely allied to it, and the Israelites certainly sprang from an idolatrous stock, for Joshua states that their fathers, who dwelt on the other side of the Euphrates, served other gods than Jehovah (Josh 24:2). Indeed, this ancestral tendency lingered among them till extirpated by the sharp discipline of the Captivity, and even after their return they could not wean themselves from dabbling in some forms of the black art.

The presence of such images, and also of magic charms and amulets implying faith in "strange gods," seemed, however, to Jacob, incompatible with his appearing as he ought before Jehovah at Bethel, on his return to Western Palestine, and they were consequently buried under "the terebinth which was by Shechem," known apparently from that time as "the Terebinth of the Diviners" (Judg 9:37 [Heb.]). But though it was thrust out from his own encampment, the patriarch could not uproot from his race the belief in their power. We have seen how Micah turned to them during the anarchy of the period of the Judges, and that his images continued to be reverenced and consulted at Dan till the Captivity. They must, moreover, have been very general even in later times, for we find David's wife, Michal, taking the household teraphim and laying it on the bed, with goat's hair over the brow, to imitate that of her husband—if, indeed, the hair of a common fly-net be not meant*—thus enabling him to escape from her father's messengers (1 Sam 19:13,14). David's house could hardly be exceptional in such a matter, even apart from the fact that he moved in the front rank of "society," and would find abundant imitation on this ground alone. Even so late as the fifth century before Christ, indeed, we find the Prophet Zechariah affirming that "the teraphim have spoken vanity, and the diviners have seen a lie, and have told false dreams" (Zech 10:2): words which conclusively prove that teraphim were in his day consulted as oracles. The earnest-souled Josiah first made a raid on these images, and swept them away for the time (2 Kings 23:24), though, we fear, hardly for a permanence, for we find that they were honoured by the Babylonians among whom the Captivity carried Israel; Ezekiel describing Nebuchadnezzar as standing where the roads parted, on one hand to Rabbath of Ammon, and to Jerusalem on the other, consulting his teraphim as to which route he should take (Eze 21:21).* Lenormant, La Magie, p. 45.

The best account of this interesting feature in old Jewish religious life is that of Ewald.* "An image of this kind," he says, "did not consist of a single piece, but of several parts, at least when the owner cared to have one of the more elaborate and complete form. The simple image, made of stone or wood, was always that of a god in human form, sometimes as large as a man, but even in early times the bare image seemed too plain. It was, therefore, as a rule, plated with gold or silver, partly or as a whole, and hence the bitter words of the stricter worshippers of Jehovah, who abhorred all image-worship, and spoke of it contemptuously as the work of the carver or the metal-founder, whose arts united in the production of the idol. Where the precious metals were plentiful enough, however, the image might be formed entirely of them. To this point, therefore, a house-god, apart from its particular form, was prepared exactly like every other idol; something added to it formed the special characteristic of the primitive house-god of Israel. To understand this, it must particularly be remembered that these house-gods were used, from the earliest times, as means for obtaining oracles, or communications from above, so that the teraphim were, in fact, strictly identical with the idols which performed oracles. To equip them for this purpose, an ephod was put on the image; an elaborate tippet round the shoulders, to which was fixed a pouch, containing the pebbles or other lots used for determining oracles, as the Urim and Thummim were hung on the breast of the high priest. A kind of mask was next set on the head of the idol, from which, apparently, the priest seeking an oracle decided by some sign whether or not the god would give a response at the time. These masks were needed to complete the image, and hence they got from them the name teraphim, a nodding countenance or living mask. At the same time, we can understand how the teraphim are described, now as of human size and form, and elsewhere as so small and light that they could be hidden under a camel-saddle; for the two chief oracular details—the ephod and the mask—were the main things, especially in a house-god, long and tenderly preserved and loved. Such, one cannot doubt, were the primitive house-gods of Israel, and if we consider the extraordinary tenacity with which everything of a domestic character held its ground, with little change, in spite of the fundamentally opposed principles of the religion of Jehovah, it is not surprising that many sought protection and oracular communications from these family idols, through centuries, fancying, however, that it was Jehovah Himself who spoke through them."* Herzog, Real. Encycl. xv. 551, 2te Auf.

From the sad spot where he buried his well-loved Rachel, Jacob wandered on towards the south, with his tents and his motherless babe—a son of sorrow to her who was gone, but the son of his right hand (Gen 35:18) to the broken-hearted father—and encamped on the way to Hebron near a tower built for the protection of shepherds and their flocks;* folds, of dry stone, with prickly bushes laid on the top of the walls, as is the custom now, being, no doubt, connected with it. Hebron and its neighbourhood seems to have been the permanent home of the patriarch, so far as his black tents, pitched on one of the slopes near, could be called home, till he went down to Egypt on Joseph's invitation (Gen 35:27, 46:1). He and his tribe differed, however, in one point from modern Arabs—they had no horses, so far as we know, though the horse was so abundant in Palestine in the time of Thothmes III, who reigned from BC 1610 to BC 1556,** that he captured 2,041 mares and 191 fillies at the battle of Megiddo, which was fought about 250 years after the death of Jacob. The Hebrews, as "plain men living in tents" in their earlier history, and as simple hill-men after their successful invasion of Canaan, never adopted the horse till Solomon introduced it from Egypt to gratify his inordinate love of display and self-indulgent extravagance. Hence they were known, among the peoples who boasted of cavalry, for their use of the ass instead of the nobler animal. There is, in accordance with this, a painting on the walls of a tomb at Benihassan, on the Nile, of the arrival, about the time of Abraham's visit to Egypt, of a Semitic family desiring leave to settle in the Nile valley: their goods being carried on asses, the only beast of burden they appear to have. It was alleged, indeed, in later ages, so identified with the ass did the Hebrews become, that, having been driven from Egypt as lepers, they were guided to a supply of water by an ass in their journey thence, and, in consequence, they worshiped the race of their four-footed benefactor. It was said, also, that when Antiochus Epiphanes forced his way into the Holy of Holies in Jerusalem, he found there the stone likeness of a long-bearded man, who sat on an ass, and whom he took for Moses. From this, the rumour spread that the Jews worshiped an ass's head of gold in their Holy of Holies. The slander, doubtless, arose, at first, from the worship of the ass by the Egyptians, as the symbol of their god Typhon, who was said to have fled through the wilderness on one of these animals.*** It is striking, however, to notice how easily the story might arise, for Abraham's ass is mentioned more than once in the Bible; Issachar was compared by Jacob to a strong ass; Achsah rode on an ass; the princes and nobles rode on asses; the asses of Kish are famous; Moses set his wife and his sons on an ass which the Rabbis have honoured with the most astounding fables; and the sons of Jacob took asses for the corn they were to bring back from Egypt (Gen 22:3,5, 49:14; Exo 4:20; Josh 15:18; Judg 5:10; Zech 9:9; Gen 44:3).* Ewald, Alterthumer, p. 297.

That such comparatively feeble creatures can stand a journey across the desert, is known to every traveller in the East. Camels are employed for the most part, but donkeys are always found as part of a caravan; and I have seen large droves of horses on the way to Egypt from Damascus. The fact is that water, the want of which is thought to make travelling over the desert wastes practicable only for camels, is found in almost any direction, in quantities sufficient for either horses or asses. Camels can bear thirst for days together, and other animals can do with far less drinking than is supposed. Only one day's journey between Palestine and Cairo is quite waterless, and any muddy brackish supply found in some desert hollow on the second day suffices. Water for human beings is sometimes carried in skins, but this provision is not needed for animals.* This is the meaning of "the tower of Edar" (Gen 35:21).

** Ebers, in Riehm.

*** J. G. Muller, in Studien und Kritiken, 1843, pp. 906-912, 930-935.

The sky over Bethlehem, the night before leaving it, brought forcibly to my mind the promise given to Abraham (Gen 15:5), when he was "brought forth abroad" from his tent and told to look up to the stars, which, innumerable as they seemed, his posterity was to outnumber. The spectacle of the heavens at night is at all times magnificent in Palestine, for the heavenly bodies, instead of merely shining afar, like gems inlaid in the firmament, hang down like resplendent lamps, beyond which one looks away into the infinite. That the patriarch should have risen so far above his contemporaries as to regard these moving orbs as the work of an invisible Creator, is assuredly to be explained only on the hypothesis of a revelation granted to him. For, even now, how inscrutable is the mystery of nature, after all our science; how complicated the theories of its origin and continuance; how profound the ignorance implied in the latest attitude of science—the simple acceptance of facts as they stand, without an attempt to rise to any intelligent first cause! That the heavenly bodies should be worshiped in such a climate as that of Syria or Mesopotamia in ages when science was as yet unborn, and motion, or impulse of any kind, seemed to indicate life, was as inevitable as the fancies of a child at the whirl of a leaf or the flow of water. Mankind were children in the infancy of the world, and their religions the religions of children. How wonderful that Abraham, bred amidst such mental simplicity, should have risen, not only above his own age, but above all ages since, outside the teaching of the Bible! It was intensely interesting, moreover, to look up, in David's own village, on the skies which he had watched with the eyes of a poet, and whose glory, as a tribute to that of Jehovah, he had sung, perhaps on the very hills lying asleep in the moonlight around me, in the hallowed strains—

A little north of the grave of Rachel part of the soil is thickly covered with stones, about the size of peas. Christ, says the legend, was once passing here, when a peasant was sowing peas on this spot, and, being asked what he sowed, churlishly answered, "Stones." "For this answer," said Christ, "you will reap stones," and from that time the ground was barren, and covered with the pea-like stones we see. Many pilgrims, travellers, and country people, were passing to Bethlehem, or going from it to the capital, some on horses, others on asses, but most on foot. A band of Americans of both sexes, young and old, rode on together to David's city in high spirits; some Englishmen were forcing their beasts into a gallop northwards; a Greek woman with a child was moving slowly forward on an ass, the husband walking at the creature's side and quickening its tired pace by rough words. Peasant-women were returning from Jerusalem, each with an empty basket on her head, stepping on bravely in their narrow blue dresses, without any thought of hiding their natural shape by any tricks of fashion, and shortening the way with loud, cheerful banter and gossip. Lines of camels, laden or without burdens, stalked with awkward, slow steps towards Hebron. The ground sinks a little after we pass Rachel's grave, then rises again as we approach the large building known as the Monastery of Elias, which is inhabited by a few Greek monks who fondly believe that the Prophet Elijah rested here in his flight from Jezebel (1 Kings 19:3), leaving his footprint in the rock as a memorial. Unfortunately, it is known that the original building was erected by a Bishop Elias, at an early date, so that the claim on behalf of the prophet is more than usually apocryphal. A comparatively fruitful valley lies below the monastery, running to the east, but the hills in every direction are as rough and bare as the most barren parts of the Scotch Highlands."O Jehovah, our God,

How excellent is Thy name in all the earth!

Who hast set Thy glory upon the heavens.

When I consider the heavens, the work of Thy fingers,

The moon and the stars, which Thou hast ordained,

What is man, that Thou art mindful of him,

And the son of man, that Thou visitest him?" (Psa 8:1-4).

The view form the monastery hill, however, is remarkably fine. To the south stand the white houses of Bethlehem on their height; on the north, beyond a broad plain, rise the walls and buildings of Jerusalem—the high, sloping top of Neby Samwil closing the view on the distant horizon; on the east the eye wanders over hills, sinking, wave after wave, towards the Dead Sea, of which part lies, in deepest azure, between these and the yellow-red tableland of Moab, which seems, in the transparent air, only a few miles distant. On the west the landscape is shut in by high ridges of hills. This spot, from which the traveller coming from the south first sees Mount Moriah, the site of the Jewish Temple, wakes the tenderest recollections in every heart that reverences the Father of the Faithful. Here Abraham, on his sad journey from Beersheba, at God's command that he should offer his only and well-loved son Isaac on Moriah, first came in sight of the hill. It was on the third day of his torturing ride from the south that, lifting up his eyes, he saw the place afar off. "Then Abraham said to his young men, Abide ye here with the ass; and I and the lad will go yonder and worship, and come again to you" (Gen 22:4,5). This must have been spoken just about where the Monastery of Elias now stands, and yet, strange to say, the monks have thought only of fables respecting Elijah, and have never realised the peculiar interest of their dwelling in connection with Abraham and his son. The land round the monastery is carefully tilled, and fenced with strong walls of dry stone, gathered with heavy labour from the surface of the ground to make it fit for cultivation. The monks have also planted fine olive-groves, and show the real benefit such a colony may be in a wild region, when industrious and intelligent. The building itself is strong enough to resist a Bedouin attack should one at any time be made.

The road sank very gently from Mar Elias towards the north, and presented the very unusual sight, in Palestine, of gangs of men at work to make it passable for carriages. Levelling, filling up, smoothing, were all in progress; the labourers swarming, in turbans, fezzes, wide "abbas," or close cotton shirts, and bare-legged, in all directions. Such a phenomenon, in any part of the Turkish Empire, well deserves notice. How long the spurt of activity will last, who gave the money, and who will get it finally, are all questions more easily asked than answered. Still sinking, the road leads gradually to the Valley of Hinnom, through stony slopes, sprinkled, as I passed, with the green of rising crops; but very different from English land, for there were, as it seemed, more stones than grain. It was the Valley of Rephaim, and promised what in Palestine is thought a rich harvest, such as it yielded when Isaiah, passing perhaps along this very track in the summer, saw "the harvest-man gathering the corn, and

reaping the ears with his arm" (Isa 17:5). But one might look in vain for the wood of mulberry-trees behind which David, thanks in part to the rustling of the leaves in the wind (2 Sam 5:22-25), was able to steal, unperceived, upon the Philistines when encamped in this valley. It was here, also, that at another time these foes of Israel were gathered when the three braves broke through their host and brought David the water from the well at the Gate of Bethlehem (2 Sam 23:13-16). The wide plain it offers for nearly two miles before one reaches Jerusalem made Rephaim, in

fact, the scene of many a fierce onslaught in ancient times between the Hebrews and their invaders.

The road sank very gently from Mar Elias towards the north, and presented the very unusual sight, in Palestine, of gangs of men at work to make it passable for carriages. Levelling, filling up, smoothing, were all in progress; the labourers swarming, in turbans, fezzes, wide "abbas," or close cotton shirts, and bare-legged, in all directions. Such a phenomenon, in any part of the Turkish Empire, well deserves notice. How long the spurt of activity will last, who gave the money, and who will get it finally, are all questions more easily asked than answered. Still sinking, the road leads gradually to the Valley of Hinnom, through stony slopes, sprinkled, as I passed, with the green of rising crops; but very different from English land, for there were, as it seemed, more stones than grain. It was the Valley of Rephaim, and promised what in Palestine is thought a rich harvest, such as it yielded when Isaiah, passing perhaps along this very track in the summer, saw "the harvest-man gathering the corn, and

reaping the ears with his arm" (Isa 17:5). But one might look in vain for the wood of mulberry-trees behind which David, thanks in part to the rustling of the leaves in the wind (2 Sam 5:22-25), was able to steal, unperceived, upon the Philistines when encamped in this valley. It was here, also, that at another time these foes of Israel were gathered when the three braves broke through their host and brought David the water from the well at the Gate of Bethlehem (2 Sam 23:13-16). The wide plain it offers for nearly two miles before one reaches Jerusalem made Rephaim, in

fact, the scene of many a fierce onslaught in ancient times between the Hebrews and their invaders.

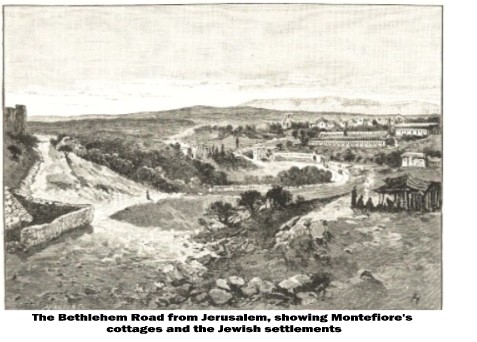

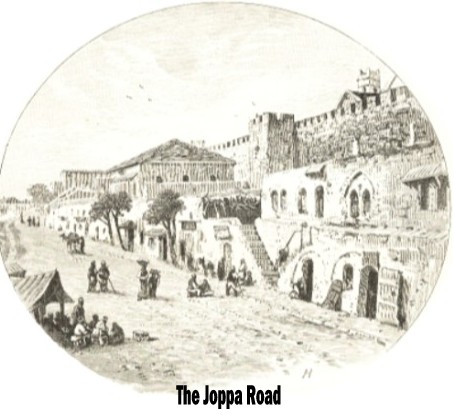

The road now crosses the Valley of Hinnom, over which the walls of Jerusalem look down, at this part, across a pleasant slope dotted with olive and other trees. The aqueduct from Solomon's Pools passes to the side of the valley next the city, just above the Lower Pool of Gihon; and our path crossed close below it, after passing a row of cottages built on the hill-side for his fellow Israelites by the late Sir Moses Montefiore. To the left, as we rose out of the Valley of Rephaim, the long upward slope of the hill, facing the west side of the city, was covered with olives; and there was also a windmill. Passing along the east side of the pool, the road kept straight north, on the east side of the valley, which was not broad; a steady rise of nearly 200 feet in all bringing us at last to the Joppa Gate, past the gardens of the Armenian monastery within the walls, and past the mossy citadel with its great slanting foundations, cut off from the road by a deep fosse, into which it jutted out in grim strength, one of the few relics of the great Herod. My feet stood at last within the gates of Jerusalem!

The road now crosses the Valley of Hinnom, over which the walls of Jerusalem look down, at this part, across a pleasant slope dotted with olive and other trees. The aqueduct from Solomon's Pools passes to the side of the valley next the city, just above the Lower Pool of Gihon; and our path crossed close below it, after passing a row of cottages built on the hill-side for his fellow Israelites by the late Sir Moses Montefiore. To the left, as we rose out of the Valley of Rephaim, the long upward slope of the hill, facing the west side of the city, was covered with olives; and there was also a windmill. Passing along the east side of the pool, the road kept straight north, on the east side of the valley, which was not broad; a steady rise of nearly 200 feet in all bringing us at last to the Joppa Gate, past the gardens of the Armenian monastery within the walls, and past the mossy citadel with its great slanting foundations, cut off from the road by a deep fosse, into which it jutted out in grim strength, one of the few relics of the great Herod. My feet stood at last within the gates of Jerusalem!

Chapter 19 | Contents | Chapter 21

Philologos | Bible Prophecy Research | The BPR Reference Guide | Jewish Calendar | About Us