by Cunningham Geikie, D.D.

by Cunningham Geikie, D.D.

Philologos Religious Online Books

Philologos.org

Chapter 22 | Contents | Chapter 24

Cunningham Geikie D.D.

With a Map of Palestine and Original Illustrations by H. A. Harper

Special Edition

(1887)

It is not easy to restore in imagination the appearance presented by the Temple in its most glorious days, but it must have been very magnificent. Even from what still remains, we cannot wonder that the disciples should have called the attention of their Master to the architecture around: "Master, see what manner of stones and what buildings are here!" (Mark 13:1). The solid wall, at one corner, still rises to a height of 180 feet above the ancient level of the ground—now buried thus deep under rubbish; at another place it is 138 feet above it; and in one spot you may see, at a height of eighty-five feet above the original surface, a stone nearly thirty-nine feet long, four feet high, and ten feet deep, which was lifted into the air and put in its place while the wall was being built. The rubbish which now lies from sixty to nearly 100 feet deep, against different parts of the walls, hides their originally grand effect; but they were bare, and in all the dazzling whiteness of recent erection, when Christ and His disciples stood to admire them.

These amazing walls were surrounded by magnificent cloisters, which were double on the north, east, and west sides; columns, of a single piece of white marble, supporting roofs of carved cedar. The royal cloisters on the south wall were still grander, for they consisted of three aisles, the roofs of which were borne up by 162 huge pillars with Corinthian capitals, distributed in four rows. The centre arch, which was higher than the two others, rose forty-five feet aloft—twenty feet above its neighbours—and the roofs of the whole, like those of the other cloisters, were of carved cedar. The front was of polished stone, joined together with incredible exactness and beauty. On all sides of the Temple, a space varying from about thirty-six to forty-five feet formed the cloisters into which, as into the Court of the Gentiles, proselytes might enter; whence its name. This was the part where the changers of provincial coins into the shekel of the sanctuary, which alone could be put into the Temple treasury, had their tables in Christ's day, and here doves were sold for offerings, and beasts for sacrifice, and salt for the altar, with whatever else was needed by worshippers: the whole a mart so unholy that our Lord, as He drove the intruders forth, declared it to be a den of thieves (Matt 21:13; Mark 11:17; Luke 19:46).* The magnificent cloister on the east side was called Solomon's Porch; its cool shade offered, at all times, attractions to crowds whom the Rabbis, and also our Lord, took occasion to gather round them from time to time (John 10:23). Hither also the multitude ran after St. Peter and St. John, when they had cured the lame man at the Beautiful, or Nicanor, Gate (Acts 3:2), on the east of the Court of the Priests.

* The Court of the Gentiles was nearly 150 feet in extent on the north and east, 100 on the west, and 300 on the south.A few steps upwards led from the Court of the Gentiles to a flat terrace, about twenty feet broad on the south side, and about fifteen feet on the others, its outer limit being guarded by a stone screen over four feet high, upon which, at fixed distances apart, hung notices, a cast from one of which is now in the Louvre, threatening death to any foreigner who should pass within. The inscription reads: "No stranger is to enter within the balustrade round the Temple enclosure. Whoever is caught will be responsible to himself for his death, which will ensue." It was for being supposed to have taken Trophimus, an Ephesian proselyte, inside these prohibitory warnings, that the Jews rose in wild excitement against St. Paul, and would have torn him in pieces had not the commandant of the fortress Antonia, on the north-west corner of the Temple grounds, hurried to his aid with a band of soldiers (Acts 21:26).

A part of the inside space formed the Court of the Women, who were allowed to walk or worship here, if ceremonially clean, but not to go nearer the sanctuary. The Inner Temple stood on a platform, reached by another flight of steps through gates from below, but by the worshippers there, and in the still lower Court of the Gentiles, only so much of the Temple itself was seen as rose above a platform nearly forty feet high, forming a square more than 300 feet long on each face, on which the sacred building stood. Seven gates opened from this into the Courts of the Men of Israel and of the Priests, and three more led into the Court of the Women. The Beautiful Gate was called also the Nicanor Gate, because the hands of the Syrian general of that name were nailed over it when he fell before the host of Judas Maccabæus; report alleging that he had lifted these hands, in contempt, towards the Holy Place, and sworn to destroy it. The name "Beautiful" was fitly given to this gate from its being made of almost priceless Corinthian brass, and covered with specially rich plates of gold. The other nine gates, and even their side-posts and lintels, shone resplendent with a covering of gold and silver. Within them rose the Temple, reached by passing through the Court of the Israelites and that of the Priests, one above the other, with flights of steps between. Beyond and above them, on the highest terrace of all, stood the Temple; its front about 150 feet long, though the Holy Place, or Temple proper, behind this, was only about sixty feet from east to west, forty feet across, and about forty-five feet high, while the Holy of Holies was a small dark chamber, not more than thirty feet square. In front of the Temple ran a porch, about sixteen feet deep, extending, apparently, to within forty feet of each side, and shut off from the Holy Place by a wall nine feet thick. Through this that awful chamber was entered by a door, before which hung a heavy veil; another of the finest texture, from the looms of Babylon, adorned "with blue, and fine linen, and scarlet, and purple," hanging before the sacred solitude of the Holy of Holies. A screen, in front of the porch, was surmounted by a great golden vine, which, it may be, our Lord had in mind when He spoke of Himself as the True Vine (John 15:1).

Thirty-eight small chambers, in two storeys, on the north and south, and three on the west, clung to the Temple on these three sides. The entrance was from the east, perhaps so that worshippers, while praying before Jehovah, might turn their backs on the sun, so universally honoured as the Supreme God by the heathen nations of Western Asia. Thus the men seen in Ezekiel's vision praying in "the inner court of the Lord's house, between the porch and the altar, with their backs towards the temple of the Lord, and their faces towards the east," showed that to "worship the sun" they had turned away from worshipping Jehovah (Eze 8:16). The great brazen altar stood, as these words of the prophet indicate, in the open space before the porch.

Such a building, rising on a marble terrace of its own, with its walls of pure white stone, covered in parts with plates of bright gold, and marble-paved courts lying one under another beneath—all held up, over the whole vast area of the levelled summit of Moriah, by walls of almost fabulous height and splendour—must have presented an appearance rarely if ever equalled by any sanctuary of ancient or modern times.

Two bridges led from Zion, the upper hill, over the Valley of the Cheesemongers to Moriah. One of these, now known as Robinson's Arch, from its discoverer, was built thirty-nine feet north of the south-west corner, and had a span of forty-two feet: forming, perhaps, the first of a series of arches leading by a flight of stairs from the Tyropœon Valley, or Valley of the Cheesemongers, to the broad centre aisle of Solomon's Porch, which, as we have seen, ran along the eastern wall of Herod's Temple. The stones, of which a few still jut from the wall of the Temple enclosure, were of great size—some from nineteen to twenty-five feet long—but all, except those forming the three lower courses, with the fine pillars that supported them, now lie more than forty feet below the present surface of the ground, where they fell when the bridge was destroyed; the pavement on which they rest is of polished stone. So deep below the level of to-day was this part of the city in the time of our Lord. Even this depth, however, in a place so ancient, does not represent the original surface, for below the pavement, thus deeply buried, were found remains of an older arch, and, still lower, a channel for water, hewn in the rock; perhaps one of the aqueducts made by order of Hezekiah, when he introduced his great improvements in the water-supply of the city (2 Chron 32:3). The masonry at the corner of the enclosure, which is ancient up to the level of the present surface and even slightly above it, shows better perhaps than any other part the perfection of the original workmanship throughout, for the blocks of stone are so nicely fitted to each other, without mortar, that even now a penknife can hardly be thrust between them. There must, of course, have been a gate through which Robinson's Arch led to the sacred area, but the present wall was built after the arched approach had been destroyed, and ignores it. About forty-three yards farther north there are the remains of another gate, which led from the western cloisters of the Temple to the city, showing by the size of the entrance when it was perfect how great the concourse must have been that passed through it, for it was nearly nineteen feet wide, and twenty-nine feet high; its lintel being formed by one enormous stone, reaching across the whole breadth, as in Egyptian temples. The extreme age of Jerusalem as a city receives another illustration in the fact that, though the gate is noticed by Josephus, its sill rests on very nearly fifty feet of accumulations over the natural rock below. It once gave access to a vaulted passage which ran up in a sharp angle from the city to the Temple area.

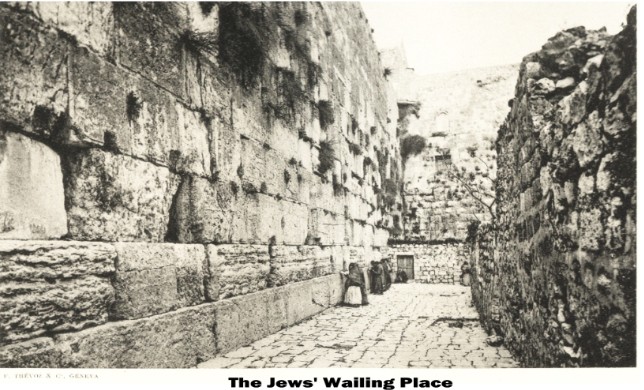

A little north of this gate is a spot of intense interest—the place where the Jews of both sexes, all ages, and from all countries, come daily, but especially on Fridays, to lament the destruction of their Temple, the defilement of their city, and the sufferings of their race. Ever since the fall of Jerusalem, the Israelite has mourned, in deepest sorrow, over his religious and national griefs, but the faith that Zion will one day rise again from her degradation to more than her former glory, is alike invincible and amazing. At least seventy feet of rubbish lie heaped over the ground where the mourners assemble, so high is the present pavement above that trodden by their fathers; but some courses of the ancient Temple wall still rise above it, and it is believed that this point is nearest to where the Holy of Holies once stood. Huge bevelled masses of stone lie in fair order one over another, defying the violence of man and natural decay. The Jews cannot enter the sacred enclosure any more than the Christians, but here, at least, they obtained many centuries ago, by a heavy ransom, the privilege of touching and kissing the holy stones. Prayer book in hand they stand in their fur caps and long black gaberdines, reciting supplications for Zion, in hope that the set time to favour her may speedily come. The Seventy-ninth Psalm is often read aloud, and is always in their hearts: "O God, the heathen are come into Thine inheritance; Thy holy temple have they defiled; they have laid Jerusalem in heaps...Pour out Thy wrath upon the heathen that have not known Thee, and upon the kingdoms that have not called upon Thy name" (Psa 79:1-6). The most touching litanies are recited; one of them beginning thus:—

the hearers, after every lament, responding:—"For the palace that lies waste;

For the Temple that is destroyed;

For the walls that are torn down;

For our glory that is vanished;

For the great stones that are burned to dust";

The Jews live in their own quarter on the eastern slope of Zion, close to the old Temple area, but their part of Jerusalem is as unattractive as their sorrows are touching. Their streets are the filthiest in a filthy city, and their dwellings among the poorest. They may have had "wide houses and large chambers, and windows cut out and ceilings of cedar, and walls of vermilion" in the days of Jeremiah (Jer 22:14), but these are traditions of a very distant past. Until recently, indeed, their condition was even more wretched than it is now, "The Israelitish Alliance" in Western Europe having afforded them systematic help for a number of years, though the first necessity, beyond question, is to teach them the most elementary ideas of cleanliness. How they live amidst the foulness of their alleys is a wonder. They are all foreigners, for during many centuries no Jew was permitted to dwell in the Holy City. Now, however, year after year, numbers come, especially from Spain and Poland, to spend their last days in their dear Jerusalem, and be buried beside their fathers, in the Valley of Jehoshaphat, the scene, as they believe, of the resurrection and of the final judgment (Joel 3:2,12; Zech 14:4). To be there saves them, they think, a long journey after death, through the body of the earth, from the spot where they may lie to this final gathering-place of their people. They come to Jerusalem to die, not to live, but many are in the prime of life and have families, and the rising generation are less gloomy in their views. The young men, in all the glory of love-locks, fur-edged caps, and long gaberdines, are as keen after business or pleasure as their brethren elsewhere, their creed evidently being a settled aim to make the best of at least the present world."Here sit we now, lonely, and weep!"

To make sure of a part in the kingdom of the Messiah, and the glories of the restored Temple and city, the Jerusalem Israelite leads a strenuously religious life, according to his idea of religion; striving with painful earnestness to fulfil all the ten thousand Rabbinical precepts founded on the Law of Moses, so as to be like St. Paul, "blameless" touching that righteousness (Phil 3:6). The Law is studied through the whole night in the schools; frivolous applications of the sacred letter being eagerly sought, in supposed fulfillment of the command, "Ye shall teach these, My words, to your children, speaking of them when thou sittest in thine house and when thou walkest by the way, when thou liest down and when thou risest up" (Deut 6:7). In the synagogue, men are found at all hours, busy reading the Talmud. The Sabbath is observed with more than its ancient strictness. From the evening of Friday to that of Saturday, no light or fire is kindled, in accordance with the injunction, "Ye shall kindle no fire throughout your habitations upon the Sabbath day" (Exo 35:3). To go beyond two thousand steps on the holy day is a grave sin, for it is written, "Abide ye every man in his place; let no man go out of his place on the seventh day" (Exo 16:29): a precept understood so literally by one Jewish sect in past times that they never rose on the Sabbath from the place where its first moment found them. Indeed, the Essenes, a sect of Jewish ascetics in the days of our Lord, would not even lift a vessel to quench their thirst on that day.* In the afternoon of each day there is preaching in the synagogues. At the Passover only unleavened bread is eaten, and booths are raised at the Feast of Tabernacles (Lev 23:6,40; Neh 8:15,16). But the most solemn day of the year is the one preceding the Jewish New Year's Day, in September. Penitential prayers are said for three hours before sunrise, and every Jew allows himself to receive forty stripes save one (Deut 25:3; 2 Cor 11:24), the flagellator saying to the person he chastises, "My son, despise not the chastening of the Lord; neither be weary of His correction. For whom the Lord loveth, He correcteth; even as a father the son in whom he delighteth" (Prov 3:11; Heb 12:5,6). On the other hand, there is great rejoicing in the synagogues at some of the other feasts, the congregation leaping, dancing, singing, and shouting, in their gladness. On some of these occasions the multitude stream forth with bright faces, men and women singing aloud, and make a procession through their quarter, with the roll of the Law in their midst. The traditions of their fathers thus live with them still, for, in some such way, David, three thousand years ago, in the same place, "danced before the Lord with all his might" (2 Sam 6:14).

If the condition of the Israelites in Jerusalem, of whom there are about four thousand, is in general very humble and wretched, it is made still harder by their frozen bigotry. Protestant missions, especially in late years, have undoubtedly made some progress, but the mass of the Hebrew population still hate the light, and cling to the great memories of the past, embittered against the whole human race. It is a striking thought, that in all probability the Prætorium, in which our Saviour was tried and condemned, lay in the quarter now inhabited by the Jews.* A great marble-paved space extended in front of it, surrounded by halls, resting on rows of lofty pillars. On a raised platform facing this square, the judgment-seat of Pilate was placed, and here the Innocent One was shown by the Governor to the fanatical mob below, only, however, to raise a wild outcry of "Crucify Him! Crucify Him! His blood come on us and on our children" (Matt 27:22,23,25). But those children were still in the vigour of life when the last hideous, despairing struggle with the Romans drove them hither, after the Temple had been burned, and turned the mansion and judgment-hall of Pilate into the scene of their final destruction. Victorious here, as already in the upper city, the legionaries cut down every one they could, till the streets were covered with dead bodies and the whole town was soaked in gore; many a burning house, if we may trust Josephus, having its flames extinguished in blood.** The descendants of that unhappy generation have built their homes over the rubbish under which Pilate's judgment-courts are deeply buried, but their souls are still bound in the same chains as then enslaved their ancestors and their darkness is still as profound.* Herzog, 2te Auf., xiii. 167.

A short distance north of the Wailing-place of the Jews are the remains of the second bridge (see ante, p. 479), which formed part of another great viaduct from the Temple grounds over the valley to Mount Zion: the most striking relic yet found of ancient Jerusalem. It is in a line with David Street, which passes over part of it, but other foundations of arches, vaults, and chambers extend, at the side of the street, for more than 250 feet from the Temple enclosure. One hall seems as if it had been a guard-house as long ago as the time of the Maccabees, and even now it is connected with a long subterranean gallery, constructed, most probably, to enable soldiers to pass from David's Tower, near the Joppa Gate, to the Temple, without being seen. A strange use of it by Simon, the son of Giorias, one of the leaders of the final insurrection against the Romans, vividly recalls the scene after the capture of Jerusalem by Titus; for by this tunnel he passed from the upper city to the Temple enclosure, trying to frighten the Roman soldiers, and thus escape by pretending to be a ghost. The Castle, or Tower, of Antonia, which owed its name to Herod the Great's flattery of Mark Antony, then his patron, stood, as has been noticed, on the site of the present Turkish barracks, at the north-west corner of the Temple area. A mass of rock, separated, on the north, from the low hill of Bezetha by a ditch 165 feet wide, and from twenty-six to thirty-three feet deep, formed the plateau from which it rose. Of great size, it was the key to the possession of the Temple, as the citadel was to that of the upper town. The rock foundation was seventy-five feet high, its face cased over with smooth stones like the lower part of the Tower of David, "so that any one who tried either to climb or descend it had no foothold." At each corner of the fort were towers; the one at the south-east, over 100 feet high, to overlook the whole Temple area, while that at the south-west had underground passages by which soldiers could be marched into the cloisters of the Temple, to quell any tumult.* Riehm, p. 699.

** Jos. Bell. Jud., vi. 8, 5.

Mount Zion falls very steeply to the south and south-west, and must therefore have been very easily defended. In the grounds of the Protestant schools, moreover, on the south-west corner, a system of rock-cisterns and a series of perpendicular escarpments of the rock, twenty-five feet high, which appear to have been continued, in huge steps, to the bottom of the hill far below, have been discovered, which show that the Jebusites, who originally held Jerusalem, spared no pains to make it impregnable. It was natural, therefore, that they should taunt David when he wished to get possession of it, telling him, "Thou shalt not come in hither; for even the blind and the lame will keep thee away" (2 Sam 5:6). A fiery spirit like that of the shepherd-king could ill brook such an insult. "Whoso smiteth the Jebusites, and hurleth both blind and lame down the cliff, shall be chief captain" (2 Sam 5:8),* cried he, in his anger, and Joab won the award. Once master of Zion, David began that enriching of it with palaces and public buildings which, continued under his successors, made it, till the destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar, the concentration of all the pomp and splendour of the kingdom, that associated with the Temple excepted. It was, apparently, on Zion that he built his palace, through the skilled aid of Phœnician architects, masons, and carpenters (2 Sam 5:11; 1 Chron 14:1); the very wood coming, in rafts, from Tyre to Joppa, whence it was dragged up to Jerusalem. Near the royal dwelling, probably, rose the barracks spoken of in Nehemiah as "the House of the Heroes" (Neh 3:16), for the Crethi and Plethi (2 Sam 8:18, 15:18, 20:7,23; 1 Kings 1:38,44; 1 Chron 18:17), who formed the king's body-guard: a band of the warlike Philistines enrolled by David for his personal defence after the subjugation of the Philistine plain. The two names seem to imply this, for they are respectively those of the first immigration of the race from Crete in the patriarchal times, and of the second immigration in the days of the Judges. Captain Conder, indeed, speaks of the Philistines as called Cherethites or Crethi, from "Keratiyeh," a village still existing in the Philistine plain, and of Pelethites as simply equivalent to "immigrants"—he supposes, from Egypt; but neither of these details disproves that the original exodus of the race was from Caphtor (Amos 9:7), which is admittedly Crete.

The ambition of the great king, true to the spirit of an Oriental, turned especially upon the construction of a grand series of rock-hewn tombs for himself and his descendants, on the south-west face of the Tyropœon Valley (Neh 3:16). There, perhaps, to this day, lie the twelve successors of David, from Solomon to Ahaz, with Jehoiada, the great high priest, but without Uzziah, who was excluded for his leprosy (2 Chron 24:16, 26:23). The tomb of David was still well known in the time of the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 2:29), but, according to Josephus, it had been opened, first by Hyrcanus, and then by Herod, to rob it of the treasures which tradition affirmed Solomon to have buried with his father.* So early as the third century after Christ, however, the true site of this "acre of royal dust" had been lost, and we can only hope that excavation may one day bring it again to light. Authorities differ as to the position of Solomon's palace, but no less an expert than Dr. Muhlau thinks it was built on the western side of the Tyropœon, and thus on Mount Zion.** On the same spot, at a later date, rose also the palace of the Asmonæan kings, and that of Agrippa II. Under Solomon the citizens had the glory of Zion increased by the magnificent "House of the Forest of Lebanon," so called from its costly cedar pillars, numerous, it was boasted, as the trees of a wood, and besides other grand buildings, by the palace of his Egyptian queen. In the days of Christ the great palace of Herod, as has been said, occupied the top of the hill, behind where the citadel now stands; its magnificent gardens, its broad waters, shaded by trees, its gorgeous halls, and the height and strength of the great wall which enclosed its grounds, with the mighty towers of Hippicus, Mariamne, and Phasael*** at its corners, making the whole one of the glories of Jerusalem. At the foot of the slope of Zion, to the east, immediately in front of the spot on which the palace of Agrippa II afterwards stood, was the Xystus, a great colonnade, enclosing an open space, used especially for athletic games after the Greek fashion, but occasionally for public assemblies, while behind it, in Christ's day, was the Council Hall, to which, as the place where the High Council sat, St. Paul was "brought down" from the Tower of Antonia, after he had been taken prisoner because of the tumult about Trophimus (Acts 22:30, 23:10, 21:29). Near this also, apparently, were the theatre, built by Herod in servile imitation of Roman manners, and the public buildings connected with the official head-quarters of Pilate, though the grand palace of Herod, on the top of the hill, was, no doubt, also used as a State building.* Ewald's reading. Keil follows it.

Amidst all this splendour of public architecture, the houses of the citizens, if we may judge from the immemorial characteristics of the East, were mean and wretched, for a despotic State in a certain stage of civilisation can boast of magnificent temples, palaces, and State edifices, while the homes of the people are, perhaps, even more wretched than in earlier and simpler times. So it was in Nineveh, Babylon, and the ruined cities of Central America, and so it is even in Constantinople at this day, if we except the houses of wealthy foreigners. Nor, perhaps, can Britain say very much when she remembers the slums and alleys of her cities. But all the glory of Zion has passed away. "Jehovah hath swallowed up all the habitations of Jacob, and hath not pitied; He hath thrown down, in His wrath, the strongholds of the daughter of Judah; He hath brought them down to the ground. He hath poured out His fury like fire; her gates are sunk into the ground; He hath destroyed and broken her bars" (Lam 2:5,9).* Jos. Ant., vii. 15, 3, xiii. 8, 4; Bell. Jud, i. 2, 5.

** Riehm, p. 684.

*** Called Hippicus after a friend of Herod; Mariamne after his favourite wife, whom he murdered; Phasaelus after his brother, who was slain in the Parthian war.

The present walls of Jerusalem were built by Sultan Suleiman in the

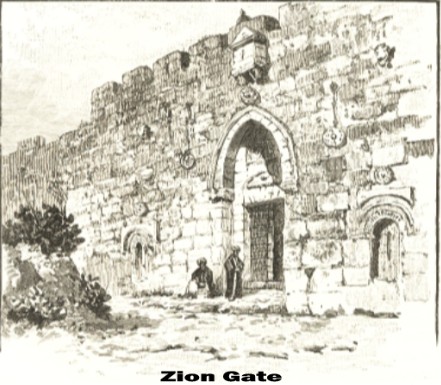

sixteenth century, and give picturesqueness, if not strength, to the town. An inscription over the Joppa Gate, and others in various places, record that the order to rebuild them was given in AD 1542;* the materials used being the remains of the older walls, which were several times thrown down and restored during the 200 years of the Crusades. The stones themselves are evidently ancient, and are all hewn, and bedded in mortar, but they are not very large. Seen from the heights around, with their towers and battlements, the walls look very imposing, though their chief advantage now seems to be the broad walk which a breastwork inside supplies, enabling one to look out on the landscape round the whole city. There are only four gates open through this antiquated defence, one on each side of the city; but there were formerly four more. Passing south, through the road in a line with Christian Street, which leads to the Damascus Gate on the north, we come to Zion Gate on the south. It is simply an arch in the wall, filled in with dressed stones, so as only to leave space for a moderate-sized two-leaved door, with an Arabic inscription over its lintel. Two short, narrow slits in the wall, like loopholes, with an ornamental arch over them, and a few rosettes and ornaments of carved stone here and there, are the only signs of its being an entrance to the city; but the wall, as you come out, is seen to be very thick. From within a dry stone wall on the opposite side of the narrow road a great prickly pear shoots out its hand-like leaves almost to the height of the top of the high central arch. It grows at the edge of a field, green, when I saw it, with barley which had been sown over the rubbish of the ancient glory of Mount Zion.

The present walls of Jerusalem were built by Sultan Suleiman in the

sixteenth century, and give picturesqueness, if not strength, to the town. An inscription over the Joppa Gate, and others in various places, record that the order to rebuild them was given in AD 1542;* the materials used being the remains of the older walls, which were several times thrown down and restored during the 200 years of the Crusades. The stones themselves are evidently ancient, and are all hewn, and bedded in mortar, but they are not very large. Seen from the heights around, with their towers and battlements, the walls look very imposing, though their chief advantage now seems to be the broad walk which a breastwork inside supplies, enabling one to look out on the landscape round the whole city. There are only four gates open through this antiquated defence, one on each side of the city; but there were formerly four more. Passing south, through the road in a line with Christian Street, which leads to the Damascus Gate on the north, we come to Zion Gate on the south. It is simply an arch in the wall, filled in with dressed stones, so as only to leave space for a moderate-sized two-leaved door, with an Arabic inscription over its lintel. Two short, narrow slits in the wall, like loopholes, with an ornamental arch over them, and a few rosettes and ornaments of carved stone here and there, are the only signs of its being an entrance to the city; but the wall, as you come out, is seen to be very thick. From within a dry stone wall on the opposite side of the narrow road a great prickly pear shoots out its hand-like leaves almost to the height of the top of the high central arch. It grows at the edge of a field, green, when I saw it, with barley which had been sown over the rubbish of the ancient glory of Mount Zion.

On the left of the gate, inside the wall, is a row of hovels given up to lepers, who, through the day, sit begging outside the gate, and at other parts round the city. Suffering from a hopeless disease, and cast out from among men, these wretched creatures live together, under a sheikh who is himself a leper. Dependent on charity, they sit in groups, apparently cheery enough; and when some one passes, they, without rising, clamour for alms, which are thrown into a tin dish on the ground before them. Now, as in the case of Job, their "skin is broken and become loathsome" (Job 2:7, 7:5) with putrid ulcers. Often, as with him, the sufferer itches all over, so that it is a relief "to take a potsherd and scrape himself withal" (Job 2:8). Often, again, the breath corrupts, so that the husband becomes "a stranger to his own wife" (Job 19:17). The disease is hereditary, but bad nourishment and a wretched home lead to its development, and possibly in some cases to its origin. There are two kinds, both found in Palestine, and both almost equally horrible. Some months before the outbreak of leprosy the victim is languid and cold, shivers and becomes feverish by turns. Reddish spots then make their appearance on the skin, with dark red lumps under them, more or less movable. In the face, particularly, these lumps run into one another, till they look like bunches of grapes. The mouth and lips swell, the eyes run, and the whole body is often tormented with itching. The mucous membrane begins to corrupt, and lumps form internally also. The eyes, throat, tongue, mouth, and ears, become affected. At last the swellings burst, turn into dreadful festering sores, and heal up again, but only to break out elsewhere. The fingers become bent, and the limbs begin to rot away. This kind of leprosy differs from what is known as the smooth leprosy, but even that is sufficiently dreadful, as it produces painful, flat, inflamed patches on the skin, which turn into revolting sores. Other diseases, moreover, are brought on by leprosy, and yet it is so slowly fatal that the sufferer sometimes drags on his wretched life for twenty years, or even more, before death relieves him. The children of leprous parents do not show the disease, generally, till they attain manhood or womanhood, but then it is certain to break out. Among the ancient Jews it was very common, yet there was only one case in the Jewish hospital in Jerusalem between the years 1856 and 1860 of a Jew suffering from it. In early Bible times it made the sufferer unclean, so that he was required to live outside the camp, while, to prevent any one being defiled by approaching him, he was further obliged to rend his clothes and keep his head bare, and to put a covering upon his upper lip, and cry, "Unclean, unclean!" (Lev 13:45). It was in accordance with this that the ten men who were lepers stood afar off as Jesus passed by, and "lifted up their voices" (Luke 17:14); and it was in compliance with the Levitical law that our Lord said to them, when cleansed, "Go, shew yourselves unto the priests." It was necessary that a leper, when cured, should go to Jerusalem, and, after examination by a priest, take part in a number of ceremonies, make certain offerings, and obtain a written declaration from the priests of his being healed, before he could go back to free intercourse with his fellows.** Year of the Flight, 920.

Under a respectable government leprosy could no doubt be extinguished in Palestine, as it has been in Britain and other countries where it was once common. But for ages the wretched beings, without palates, or with no hands, or with swollen and hideous faces, have been allowed to marry and live together, at the gates of Jerusalem, perpetuating the plague in their unhappy offspring. Nor is it confined to the Holy City. Lepers are found over the whole country. Precautions are, indeed, taken to guard the healthy, but as leprosy is not contagious, these are in reality of no value. In Bible times, any one thought to be attacked was shut up, and removed outside the city on the disease showing itself; he, his clothes, his very house, and everything he touched, being pronounced unclean. Nowadays, he may, perhaps, be allowed to live immediately inside the gates of Jerusalem, but he has still a separate dwelling assigned him, and every one keeps aloof from him as polluted and dangerous. Nor will any one touch a leper, or eat with him, or use anything he has handled. Arabs thrust a leper away from their encampments.* See Geikie, Life and Words of Christ, ii. 12-15.

The prevalence of leprosy among the ancient Jews gave a strange colour to the fancies of the Western nations of antiquity respecting them. Tacitus thus gives the various opinions afloat concerning them, viz., that Crete was their original home, its great mountain Ida being the source of their name, "Judæi"; that they were a colony of Egyptians who emigrated, under the leadership of Hierosolymus and Judah, through the pressure of population of the Nile; that they were Ethiopians whom fear and hatred forced to leave their country; that they were an Assyrian race, who, having no lands, established themselves in Egypt, and finally spread to Syria; and, lastly, that they were the descendants of the Solymi, a nation famous in Homer; whence the name of their capital, Hierosolyma. All this, however, he owns to be doubtful. What is more generally admitted, he continues, is that Egypt being infected with a kind of leprosy which covered the whole body, the king, after consulting the oracle of Ammon respecting the means of removing it, was ordered to purge his kingdom of lepers, who seemed hateful to the gods, and to send them off to other lands. All the diseased, having therefore been searched out and collected, were left in the midst of the desert. On being thus abandoned, they gave way to despair, except one, Moses, who urged them to look for help neither from the gods nor from man, since they were abandoned by both, but to put their faith in him as a Heaven-sent leader, promising that, if they followed him, he would deliver them from their miseries. To this they agreed, and began their march, ignorant of the way or its dangers. Nothing, however, distressed them as they went on so much as the want of water; but when they were in extremities, sinking, exhausted, along the whole line of march, a herd of wild asses passed from the open field to a rocky place, hidden by woods, and Moses, having followed, in the thought that the richness of the grass boded the nearness of springs, discovered great fountains of water. This saved them, so that after a further continuous march of six days, they, on the seventh, having defeated the inhabitants, won the land in which are their city and Temple.*

All this is so curious that perhaps I may quote a little more. To put the nation thoroughly under his control, says Tacitus, Moses gave them an entirely new religion, the opposite of that of any other people. In it all is abhorred which we revere, and all is revered which we abhor. An image of the beast which had relieved their thirst and saved them, was set up, as sacred, in their Holy of Holies. They sacrifice the ram, as if in contempt of the god Ammon (who was ram-headed), and for the same reason they offer up the ox, which the Egyptians worship under the name Apis. They abstain from pork, in memory of the shameful disease under which they suffered so terribly—a disease to which the pig is liable.** Tac. Hist., v. 2, 3.

Much in this is, of course, fanciful, but it is certain that the Hebrews brought leprosy with them from Egypt, for at the very commencement of their forty years' wanderings, Moses commanded that every leper should be put out of the camp (Num 5:2), and the disease could not have been brought on in the wilderness. It had, therefore, no doubt, broken out through their miseries while in Egypt, which we may the better imagine when we recollect that Josephus speaks of their having been sent to quarries on the eastern side of the Nile, to cut out the huge blocks used in Egyptian architecture.* There, he tells us, "they remained for a long time." Condemnation to the hideous slavery of this life was a usual punishment under the Pharaohs for criminals and all who gave the State trouble, the unfortunates being banished to the quarries with their wives and children, without regard to age, even their relatives sometimes sharing their fate.** In later ages, great numbers of Christians, many of them of prominent social position, were thus condemned to the porphyry quarries between the Nile and the Red Sea, and others were sent to those in the Thebais.*** The unspeakable wretchedness of an existence in such burning craters as these quarries must have been, without care, shelter, or sufficient food, and with unbroken toil under the lash, may well have lowered the system, till leprosy and diseases of similar origin took wide hold of the sufferers.* Tac. Hist., v. 4.

That leprosy was very common among the ancient Jews is in any case certain, for their laws are very full and stringent with respect to it, and enumerate various forms of the disease (Lev 12, 14). They even speak of leprosy in woollen or linen garments, or in leather, and, still more strange, in houses, but it seems probable that these passages refer to skin diseases resembling leprosy, and which are therefore classed by Moses with it. It is well known that many such skin ailments, which to the untrained eye may easily be confounded with leprosy, spring from microscopic vermin (Acari), or from the minute sporules of some kinds of fungus, and both these sources of dire calamity cling to garments and to household utensils, and even to the stones and mortar of a house. This appears to be the true explanation of the Levitical laws respecting "leprosy" in inanimate substances, and they were clearly wise and philosophical, for modern science is no less concerned than they were with germs and their propagation.* Jos. Cont. Ap. 1. 26. Tacitus appears to have used Manetho, from whom Josephus quotes, or perhaps he quoted from Josephus, who flourished AD 38-97. Tacitus lived AD 61-117.

** Ebers, Durch Gosen, p. 155.

*** Eus. Hist. Eccles., viii; Martyrs of Palestine, c. 8.

A comparatively broad street leads first west, then north, from Zion Gate to the open space before the Tower of David. On the south lies the ploughed field, over the wreck of the past; on the west, after turning the corner, you see the great gardens connected with the Armenian Monastery, which provides accommodation for several thousand pilgrims. The church belonging to this establishment is grand with lamps, carpets, pictures, and gilding. A fine house for the Patriarch is appropriately connected with a cemetery in which all his predecessors lie buried. The monastery is said to stand on the site of the house of the high priest Caiaphas, and, in keeping with this veracious tradition, the stone which closed the Holy Sepulchre is shown under the church altar, and the spots pointed out where Christ was in prison, where Peter denied Him, and where the cock was perched when it crew, though the surface of the Jerusalem of Christ's day, as I have mentioned, lies buried beneath many feet of rubbish. It is pleasant to look away from these monkish stupidities to the glorious gardens, the fairest in Jerusalem, with their tall poplars and many other kinds of trees waving above the city walls.

Just before reaching the open space at David's Tower, a short way from the street, on the right, is the English Protestant Church, for the English-speaking population, which mainly consists of visitors. It is only within a few decades that Evangelical religions has obtained such a permanent footing in the Holy City, but since it has become naturalised, if I may so speak, it has attracted a steadily-growing interest in the country. The time is past when a devout soul like Luther could think that God cares just as much for the cows of Switzerland as for the Holy Grave which lay in the hands of the Saracens. The great importance to the intelligent study of the Bible of a closer acquaintance with Palestine is universally recognised, and the land of Holy Scripture has been felt to have claims on the loving interest of all Christians, as that from which the salvation of the world went forth. The Jewish Mission, of which I have already spoken, was the fruit of this newly-awakened enthusiasm, though experience seems to show that Jerusalem is precisely the most unfavourable sphere for its success. But preaching to the Jews is not the only form of local Christian activity. As it was desirable to raise the spiritual condition of native Christians generally, by a diffusion of simple Evangelical truth, Prussia and England in conjunction, at the suggestion of King Frederick William IV, founded a bishopric, to give Protestantism a more imposing representation in Jerusalem. The present church also was, after a time, built, chiefly with English money, and Prussian and English Consulates were established, giving additional weight to the Reformed creed. Hospitals for Jews, and also for all nationalities, without distinction, have been founded and are in active operation, showing, perhaps more strongly than anything else could, how true and deep is the interest Evangelical religion takes in all human sorrows. A child's hospital has been established by Dr. Sandreckski, an accomplished Prussian, and is maintained at his own risk, the subscriptions towards it being often deficient. I visited it and the English hospitals, and can honestly praise them both, though I confess that my heart went out most tenderly to that for children, which was filled when I went through it. The Germans also have a hospital for themselves, admirably managed. Evangelical missions of other kinds are not wanting, and it is only right to say they could in no place be more needed.

If the rigorous observance of religious forms, including prayer and the worship of God, were enough, Jerusalem might be pronounced, in fact as in name, the Holy City. It is the same with the Jew of to-day as with his ancestors, who wearied themselves with offerings and other external observances, but were so corrupt and morally worthless as to rouse the bitterest reproaches of the prophets. "Rend your hearts, and not your garments," cried Joel, "and turn unto the Lord you God" (Joel 2:13). "The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit," sang the Psalmist (Psa 51:17). Such prophet voices are no less needed in Jerusalem now. Conscience seems asleep; the moral sense dead. That it is possible to trade without lying and fraud is as monstrous an idea to the Oriental to-day as it was when Jesus the Son of Sirach wrote, "As a nail sticketh fast between the joinings of the stones, so doth sin stick close between buying and selling" (Ecclus 27:2). The first consideration of the vendor is the extent to which he may presume on the simplicity of his customer, and so skilled in trickery are all traders alike—Moslems, Christians, and Jews—that the webs of lies they spin, and the depth of their wretched cunning, are entirely beyond the conceptions of the Western world. Indeed, they even boast of their cleverness in lying. Nor is this the only great sin infecting the community, and condoned by the corruptness of local public opinion; meanness, pettiness, and baseness are so common that it must be very hard to walk uprightly and without hypocrisy in Jerusalem.

It is to the lasting honour of Bishop Gobat that he saw the necessity of religious education to raise the moral tone of the Christian population. His school-house, a stately building, stands immediately above the steep descent of Mount Zion. It was founded in 1853, and when I visited it had forty-five boys and thirteen youths, who might be called students, but no day scholars. This is a much smaller attendance than at the American college at Beyrout, but perhaps the locality is less favourable. There is, besides, a school for girls in the city, with seventy on the books when I was in Jerusalem; this is a day school. The Germans also have training schools. To the east of Bishop Gobat's school lies a pleasant garden, divided by a wall from the English burial-ground. In laying out this, vast masses of rubbish had to be removed, and a broad terrace was thus laid bare, cut off on the north from the higher rock by a perpendicular escarpment. Fragments of the old wall of the city still remained on the top of this escarpment when it was first uncovered, and a number of hewn stones lay around. There are, moreover, remains of a rock-hewn stair, and, as I have said, a number of rock-hewn cisterns, with a round hole in the covering through which the old Jebusites once drew up water. The stair without question formed a comparatively secret way from the city walls to the bottom of the valley.

The streets of Jerusalem, like those of all Oriental cities or towns, are left at night in total darkness, except where a feeble lamp, hung out by a kindly householder, sheds a glimmer for a few yards. Nor is there any cheering light from the houses themselves, for there are no windows except high up, and the thick lattice shuts in any feeble beam there may be in a few higher chambers. No one, therefore, can move about without a lantern, since to do so would ensure a speedy fall over the rough stones, or headlong precipitation into some gulf; not to speak of dangers from the town dogs, and the nameless filth of the side streets. It is, therefore, obligatory to carry one's own light, and any one found abroad without a lantern after nine o-clock is at once stopped by the turbaned curiosities who do duty as watchmen.

The population of Jerusalem is about 30,000, who are divided and subdivided into no fewer than twenty-four distinct religious parties, more than half of which are Christian, the whole showing anything rather than brotherly love to each other. It has often been a question how the vast multitudes who in ancient times thronged to the Passover found room in a place which the configuration of the ground prevented from ever being much larger than it is now; but we have, at least, a slight help towards understanding the possibilities of an Eastern town in this respect in the sights presented at Jerusalem each Easter. Thousands of pilgrims of all the Oriental Christian nationalities are then in the city, and at the same time vast multitudes of Mahommedans arrive from every Moslem country, and even from India, to pray within the sacred enclosure on Mount Moriah; the object of the institution of this counter-pilgrimage, if one may call it so, having been, apparently, to secure the presence in the Holy City of a great body of "true believers" when the Christians were assembled in force. At these times every khan, convent, and lodging-house, is crowded, tents are pitched outside the walls, and all available spots within the city are used for sleeping-places by the poorer pilgrims, who cook their simple food in the open air, and lie through the night in the streets. The open space before the Tower of David is a favourite spot for this bivouac, men, women, and children cowering as closely as they can on its rough stones. It must have been the same in ancient Jerusalem, but there was the great additional aid that every family opened its rooms, and even its roofs, to pilgrims, inns being then unknown. Besides, a convenient fiction of the Rabbis extended the sacred limits of Jerusalem during the feasts as far as Bethany, so that the thousands who could find no space inside the walls had ample room without them.

Chapter 22 | Contents | Chapter 24

Philologos | Bible Prophecy Research | The BPR Reference Guide | Jewish Calendar | About Us